Editors Battle Advertisers for High Ground

The editor was showing off the latest issue of his glossy business magazine. Big. Bulky. Packed with full page ads. Everything shouted one vigorous message: Business is great.

Paul Conley shook his head—inwardly, at least. “I didn’t have the heart to tell him all those ads were ‘make goods.’”

Grim anecdote, true. But emblematic of today’s print world, according to the veteran publishing consultant and VP of CFO Publishing. If Conley has seen many publishing trends come and go, the latest ones all seem to be pointed in one direction: down. “Things are getting worse and worse.”

Making good

The culprit is the same Internet shift gnawing at industries from newspapers to recording artists to business supply stores. Print magazine publishers, for their part, are trying a number of techniques intended to shore up profits. The problem is that advertisers are not happy with the results.

“Advertisers tend to find b2b disappointing,” reported Conley, speaking at last month’s annual conference of the American Society of Business Press Editors (ASBPE). “Not the editorial content, but the business model. That makes it harder to monetize what we do on the editorial team.”

Solutions, though, seem few. “Banner ads were doing okay for awhile, but no one is doing too well with banner ads anymore,” noted Conley. “Then publishers moved toward ‘lead generation’ sales. But lead gen is not working.”

Magazines are resorting to spamming their audiences while advertisers demand ‘make goods’ for ads that fail to pull in the promised leads. Hence the happy but hapless editor in this article’s opening story. “Sales people know about the problem but editorial teams do not,” said Conley. “They have no idea how bad things have become.”

Enter Native Advertising

Like a life saver dropped to a drowning man comes the shout of a desperate captain: Sell editorial!

No one will use those exact words, preferring the more ethically sheltered sobriquets of “native advertising” and “content marketing.” Whatever the terms, they suggest for editorial a certain shifting of ground. Publishers are seeking a way to monetize their product in a way that capitalizes on the faith readers have invested in the sacred space of the editorial temple.

“The worst piece of news I have is that that the battle for the integrity of the editorial stream is lost,” said Conley. “We lost that battle largely because people on the editorial side were not paying attention. They did not know the battle was happening. So advertisers will continue to put pressure on publishers. You will see this soon in your brand. You will either make the adjustment or your brand will continue to stumble.”

Just what is native advertising? Definitions vary by aspect, but those with deep pockets have the idea that money talks. Conley reported that in a recent emarketer.com survey, nine of 10 North American manufacturers agreed with this definition of native advertising: Content produced for or by the advertiser that runs within the editorial stream. “Not along the side,” noted Conley, “but within space that has traditionally been sacred to us. Their content runs there. That’s what they want because that is what’s working for them today.”

Rules of the Game

Intrusions by advertisers into editorial are something of an irony: Any benefits gained rely on that very tradition of an editorial cathedral the money changers threaten to sully. One might posit that at some point, when the purity of editorial is gone, the power of native advertising will diminish.

Editors, however, can take steps to maintain their integrity while acknowledging the new realities. Conley suggested setting ground rules. “This is where I want the next battle to be fought: When a publisher says we are going to do native advertising, editorial says ‘This is how we do it and it is not negotiable.’”

Conley presented the following four rules “to comfort editors, restrain the ad sales staff and make clear to media partners what you expect.”

- Native advertising must be transparently identified as an ad, even if it is in the well.

- Native advertising must be congruent with the publication’s mission.

- Native advertising must be interesting and have good copy. Editorial will decide these matters of judgment.

- The editorial staff must not work on the product. “There are a lot of really talented people that can help advertisers,” noted Conley. “Find them. Get a freelance stable and find out which ones will work with advertisers. Segregate your freelance staff.”

Going rogue

Some advertisers are bypassing the traditional editorial stream, carving out their own channels to readers. “Brands are doing their own content, getting away from us and what we have traditionally offered them,” said Conley.

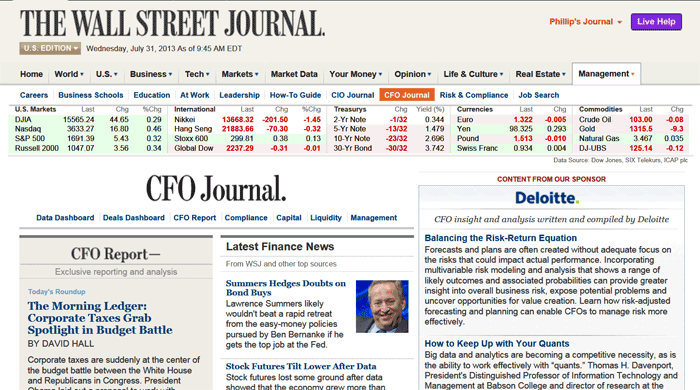

An example of this is the Deloitte native advertising column that appears on the right hand side of The Wall Street Journal’s CFO section. The term Sponsored Content appears over the column of native advertising. Beneath it are the words: Please note: The Wall Street Journal News Department was not involved in the creation of the content above. If readers overlook such caveats they will be impressed by the quality of the work. “It is really good stuff,” said Conley. “They are producing stuff that I cannot argue for a second is inferior to what we do at CFO.”

The Deloitte column is just one example of an industry that has become fragmented. Other brands are starting their own tablet formatted industry magazines. New Internet vehicles are popping up, puncturing old verities and appealing to an interactive audience.

Here are some examples of feisty competitors: www.skift.com; http://www.bisnow.com/, and http://www.industrydive.com/

The b2b market, in brief, has become wildly competitive. “The old rule was that there were always three brands in every space: the market leader, the number two publication, and the new challenger,” said Conley. “Since there were only three places to get information the advertisers had to deal with us. That’s simply not true anymore.” And the more money brands put into captive editorial, produced by writers sometimes referred to as “embedded journalists,” the less money is available for advertising in traditional b2b vehicles.

At the same time, many new vehicles are producing material that is far more compelling than old b2b media’s mix of copy and pix. That can be a game changer in terms not only of profitability but also of business publishing in general, said Conley. “When was the last time you saw something in b2b that inspired you, that shook you up, that moved you? That you saw something you had not seen previously, that was truly revolutionary? When was the last time you saw something that made you walk across the office and say ‘did you see this?’ That was never a common experience in b2b. It is now.”

Aliens in the stream

A new breed of creators, better at making value and building audiences, is now challenging the world of traditional publishing. “The newer companies which are doing the moving, surprising work in b2b have a couple of things in common,” said Conley. “First they are driven by Gen X and increasingly by Gen Y. These people have lived their whole lives creating media, not just consuming it.”

Traditional executives are not prepared to compete. “Publishers are print centric, nostalgic, and are not adjusting well to the digital world,” said Conley. “And they are living within a financial structure that does not require them to be innovative. Private equity dominates the ownership of b2b. Private equity is not a business model; it is a wealth accumulation model. It’s about taking money from products for the investors, then growing the products and taking more money from them.”

That’s a recipe for short term thinking. Indeed, publishing executives very often look to flip their properties rather than spend years building a brand, said Conley. “It’s very hard to talk to those people about innovation, about investment in the staff, or about what the company will be like in 20 years.”

Anchored in text

Editorial, for its part, has also been reluctant to move forward. “We are still stuck trying to perfect the things that were important 10 years ago,” said Conley. “We have perfected print. Print is perfect.” At the same time, editors and writers are failing to master new media’s requisite skills. “We cannot edit a photo, cannot upload a video, don’t know how to record an audio. It’s extraordinary to me.”

Any editorial room conversation about the digital media tends to concentrate on old issues. As an example, Conley pointed to the continuing argument about the risk of external links causing visitors to leave a magazine’s site. That dialog is stale; the Internet has moved on. “As long as we continue to fight the battles of 10 years ago we will be unable to fight the upcoming ones,” said Conley.

Editors and writers must become more sophisticated about digital publishing, for the sake of their careers as well as their employers. “The younger people who are starting the new media companies are hiring entirely different kinds of journalists,” said Conley. “They come with new attitudes and new skill sets. It is a 100 percent cultural difference from five years ago. It makes it hard for older people like me to compete for money, attention, jobs, gigs. Younger people have a skill set I cannot duplicate.”

That, however, does not spell the end of careers. New skills can be acquired by those who are determined to do so. Reliability, revered for decades as paramount to success, is as vital today, and perhaps as scarce, as ever. Just as important, though, is flexibility: Cultivate a mind open to new media and digital procedures.

But editors and writers must do still more: They must heighten their public profiles. “It will be a lot easier to market yourself in the future if you become a leading voice in your area of coverage,” said Conley. “Move from being a reporter to being an analyst. Be media friendly. Be the person the press reaches out to on your topic. Create a personal brand.”

Photographs and text by Phillip M. Perry

August 2, 2013